Day 4 at Giornate has left my head bursting with so many new thoughts and ideas!

It has also left me full of optimism for the future of older films. A real eye-opener for the day was the bonus Collegium dialogue on digital archiving. I was slightly worried going into it, as I was worried that it would be a session chock full of jargon only comprehensible to advanced technical archivists, as I’m pretty much uninitiated to much of it as just a guy who has never even been in film archive. (even though this week involved hanging around archivists from all around the world, all day, everyday.)

To kick off this eye opening session- pun intended- was Jeroen de Mol from the EYE Filmmuseum in Amsterdam. They went on to talk about the absolutely wonderful digital archiving system that they are working on – EYE-D (pun also intended, on their part). Without using too much technical jargon, their new digital archive in progress is essentially a program with search engine, streaming and intuitive capabilities which enables you to not only watch their entire archive of films (given that you are granted permission from your computer), but you can also upload films to their archive with a few clicks. Uploading a film creates a new streaming link for it on their specially developed video player, which is partly based on the metadata of the upload which gives the stream the correct framerate, and so on. You can also easily pause at individual frames of the film. When a film is uploaded, it is also transferred to an LTO-harddrive (a longer lasting type of hard drive compared to the one in the computer or mobile device you’re reading this from) for backup via a robot, so that it is not at the complete mercy of the one digital copy being made in front of you. Every step of the process is logged automatically for extra safety and backing up, just in case. Especially with older films, a “just in case” contingency plan is always a good thing.

If you are getting a film, but not interested in the whole film, the video player can easily let you select the parts you found interesting (so perhaps cutting out the latter half of yesterdays Sao Paulo city symphony) and put it in your own personal “shopping carts”. This «shopping cart» is perhaps my favorite feature of the whole system, as you can create your own databases in your account in their archive of films or clips of films that fit what you are after – this can also be shared with others via a simple customized direct link with a button. The search engine part of the system should not be ignored either: “Googling” a film in a digital archive makes life much easier for anyone who needs or wants to check find a specific piece within an archive.

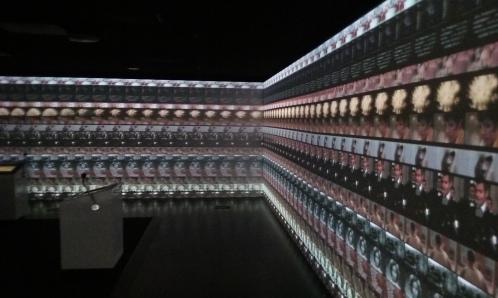

All in all, this type of intuitive, easy to use digital archiving saves everyone a lot of time, and if all the tens and thousands of films and other materials in a large archive like EYE becomes digital and searchable, it will become much easier to see the possibility of every piece of archival material could be identified, tagged and accounted for in meaningful ways – unlike a lot of the material today. That’s part of why rediscoveries in festivals like the Pordenone are rediscoveries: they were mislabelled or unindentified films in archives that they didn’t even know they had, until someone opened the cans of film again, and by luck or chance, knew and recognized what they were seeing. Because streaming and searching on a computer is much faster, the rediscovery process should be a lot faster. Image recognition software is also going places, and will likely be a helpful tool in the future in identifying unidentified films through perhaps, image-matching searches, or image based search algorithms. All the data in a digital archive can also make it easier to do big-data and empirical research in the film sciences.

All of the EYE digital film museum will not be available to everyone however, because of copyrighted material. But then again, there is plenty of archival material that either does not have any owner, or in some cases, expired or ambiguous rights status (most likely because there are no current monetizing incentives involved for those particular archived items).

Here’s where the second presentation of the bonus Collegium dialogue comes in. David Pierce and Eric Hoyt has started a project (Media History Digital Library) to make film magazines that do not belong under the present copyright law accessible to everybody, and the database is entirely searchable. At http://lantern.mediahist.org/ , I did a quick search for the film Janko the Musician (Ordynski, 1930) and found out that according to the American Cinematographer’s October 1930 edition, it was the first multi-lingual Polish production, as they were making four (!) versions: a German, a French, a Polish and an English version. Open, accessible and easily navigated projects such as this is useful for more than sourcing for fun facts for a film blog – it could potentially be very useful for reception studies and film historians. On a symbolic level, it is also quite important in its efforts to save as much as we can from the past, as corporeal film archives can easily disappear in a flash (or slowly deteriorate over time). Or go up in flames. Literally.

Nanà (Camillo De Riso, 1917) was a film shown today that has been saved (well, partly) from slow destruction quite recently, believed to have been completely lost. Like the 1926 Jean Renoir version screened later in the evening, it is based on the 1880 novel by the same name by Emile Zola. One can easily understand the appeal of creating several versions of this film: in it, we see a woman from a very humble background gradually make her way to become a high-class prostitute, destroying any men who get in her path. The 1917 Italian film was initially regarded as suitable for mass audiences, but as rumours spread before its launch about the risqué and adult nature of the film (which showed the silent firm siren Tilde Kassay in her prime seducing men), it eventually ended up being confiscated a few hours before the first screening. Of course, the salacious nature of the film is regarded as very mild by today’s standards, but one can see from the one-third of the film that survived that it is fairly sexual. It comes off as a milder version of a Danish 1910s circus and attraction films (featuring Asta Nielsen), but because it was partially set in high society, it became more difficult for it to pass through censorship in its time.

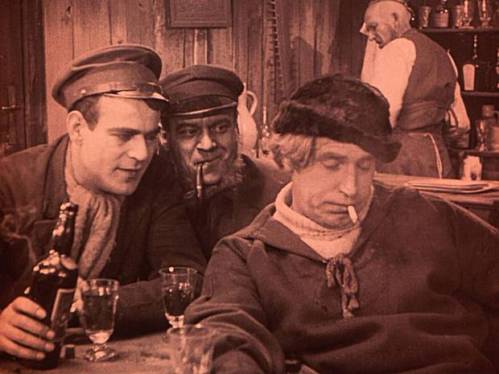

Because so much is lost from the 1917 Nanà, it is difficult to engage it in a fair comparison with the Jean Renoir film, and Jean Renoir is Jean Renoir, so very few can compare. He wasn’t that big of a name when he made his third film however, and Nana (1926) flopped at the box-office, which meant that Renoir could not produce as films with as extravagant a budget for the next decade or so – until La regle du Jeu / The Rules of the Game (1939), which was also a critical and commercial flop, until it was canonized much later. Nana (1926) is not that well-known and is therefore a good target for the Pordenone film festival for a rediscovery. It is probably not going to be considered essential work anytime soon, however it was a very enjoyable watch.

Another enjoyable watch was the last screening of the day, The White Desert (Die Weisse Wüste, Ernst Wendt, 1922) a peculiar German film set in a harsh Nordic environment, a so-called Schwedenfilme – a mini-genre that was popular among German critics in the silent era. It is partly shot on location in Sweden, and has characters with Nordic names like Sigurd, Björn, Signe and Nora. It has also, rather randomly, included all sorts of animals like reindeers, foxes, sea lions, a real polar bear and a man in a bear suit. This is in large part due to it being a Hagenbeck production, and the Hagenbeck family was world famous for their animal (and human) zoos, and saw film as an area for magnificent displays of animals. It is far from being a truly great film, and it seems to lose its way because it’s adamant on using all the animals on the set, even if it does not make sense. I had fun with it however, as a curiosity piece from the Weimar Republic. Props to the accompaniment for this screening, Günther Buchwald and Frank Bockius, as they gave the film an extraordinary treatment. I was particularly fond of how they brought life to the ice, making it “feel” like ice, sending shivers down my spine, making me feel cold as I was watching it. Film is supposed to be felt too, and the disconcerting tones they created made me uncomfortable in a “good” way, and enriched the experience by lending a very tactile and tangible corporeality to the films being shown.